Excerpted from Chapter One of Lessons in Astrology as Magic by Dana Gerhardt

Shadows can erupt at the most inconvenient moments or sabotage us quietly over time. They might also bring great gifts. Living at the fringes of our nature, they break the rules, assault our values, yet owing to their outlaw status, can bring new creativity and important messages. We can learn from our shadows. So let’s slip off our lab coats and step into the parlor of the phony teller. What hidden aspects of our own practice might we find?

With her dangly earrings and flowing scarves, the fortune teller is definitely more Neptunian than Uranian. She can be mysterious and vague, slippery or flakey, thoroughly deceitful, or prone to a fawning cultivation of spirituality and fame. Of course astrologers are never like this! But speaking for myself, I’ll admit there have been moments, particularly when a chart is puzzling, that I’ve found myself behaving like a fortune teller, drawing information and guidance out of thin air. My body tingles, I see a fuzzy inner image, I hear an odd word or phrase, having no idea where this comes from, yet I give it voice and pass it off as knowledge. Often it is helpful to my clients.

What makes a fortune teller phony? That she claims to speak with spirits? That for extra cash, she’ll promise to reverse a curse? Or is it that we don’t always understand—let alone value—her mysterious techniques?

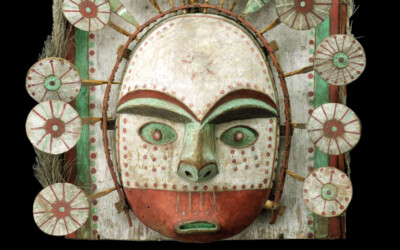

Shadows hide talents too. When we say an astrologer’s work is science and nothing like a fortune teller’s, we deny ourselves access to her positive Neptune gifts, her sensitivity, intuition and imagination. We succumb to the materialism of our day and lose kinship with her predecessors, the ancient magicians, sorcerers, shamans, and healers who weren’t content just predicting futures—they aimed to shape them. Through rituals, enchantments, and altered states, these individuals could open the gates between the worlds and summon the assistance of more-than-human powers. But that was long ago. Are such things still possible?

Sorcerers and shamans disappear from a culture about the time the spirits leave its trees, when its mountains and birds stop talking and its gods withdraw to the heavens—in other words, when its people no longer tend to the invisible presences that surround and support their world. A society thus starved of its relationship with natural forces might send its own rejected powers into darker archetypes like the Witch. Here’s another shadow worth unpacking. What can the Witch teach us about practicing magic?

Consider the great Slavic witch Baba Yaga. In myths and legends whenever she appears, a terrible wind blows, the trees groan, spirits wail and shriek. Her eyes burn like hot coals. Her nose touches the ceiling when she sleeps. She flies in a giant mortar and steers with a great pestle, her bony knees touching her chin; behind her, a silver branch keeps erasing her tracks. She kidnaps children and eats them. She throws visitors into her soup. She can heal the sick or grant boons to honest petitioners, but few dare approach her. Deep in the forest behind a fence of human skulls, she dwells in a windowless hut that dances on chicken legs.

Consider the great Slavic witch Baba Yaga. In myths and legends whenever she appears, a terrible wind blows, the trees groan, spirits wail and shriek. Her eyes burn like hot coals. Her nose touches the ceiling when she sleeps. She flies in a giant mortar and steers with a great pestle, her bony knees touching her chin; behind her, a silver branch keeps erasing her tracks. She kidnaps children and eats them. She throws visitors into her soup. She can heal the sick or grant boons to honest petitioners, but few dare approach her. Deep in the forest behind a fence of human skulls, she dwells in a windowless hut that dances on chicken legs.

Northern hunters and nomads used to build windowless cabins on tree stumps (their spreading roots looked like chicken legs); it was a clever way to keep foraging animals from stealing their supplies. Siberian pagans built smaller versions of the huts to hold their sacred offerings of bone-carved dolls (whose noses touched the little ceilings). It’s easy to surmise that before Baba Yaga flew on her mortar into so many myths, there were actual wise women living in the forest, mixing herbs, boiling potions, carving dolls, and casting spells for those who sought their help. But why were such terrible stories circulated about them? It’s enough to make our own eyes burn like hot coals: good witches get no respect!

How many centuries have the intuitive arts suffered! How many witches have been burned at the stake? Indeed, when I started lecturing on practicing astrology as magic a year ago, a few people warned me that it might not be safe—there are still laws against it. We come again to our war with the culture, which I still leave for others to fight. My interests remain with our shadows. It’s true that a good witch or teller is by definition a “sensitive” and therefore needs the protection of strong boundaries. But the Martyr/Victim archetype (which likes to hover around us Neptunians) invokes just the opposite. It can send us into a defense-weakening trance that will empower our enemy’s curses. It’s better to focus on protection, which takes us back to Baba Yaga’s tale.

Stories about sorcerers and magicians are often written in code. They are lies—designed to discourage careless or untrustworthy visitors. They ensure the mystic healer won’t be bothered until the patient has exhausted all other options. Such was the discovery of the cultural ecologist David Abram when he studied with traditional shamans in Bali and Nepal.

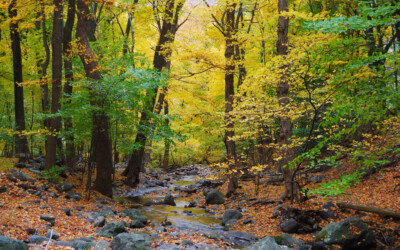

In his remarkable book on natural magic, The Spell of the Sensuous, Abram noted that the dukuns never lived in the heart of the village. They always lived on the outskirts—in the jungle, the forest, a rice field, or a cluster of boulders—somewhere between the village and the wilds of nature. Nasty rumors often swirled about them, which the shamans never bothered to dispel. Fear bought them a necessary privacy to perform what they considered their main work. Their real job wasn’t healing the villagers; it was ministering to the larger forces of nature on which the entire village’s health depended.3

The shamans worked as intermediaries, says Abram, ensuring a proper flow of energy and nourishment not only from land to people, but from the people back to the land. Through the dukuns’ prayers, propitiations and praise, they kept the balance between the worlds. This work required a regular shedding of ordinary consciousness and entering into altered states. Through trances and visions they could communicate with the inhabitants of their spiritual neighborhoods, listening to and learning from these other forms of consciousness. Without these sacred conversations, there could be no healings, as the natural world was the source of health, just as sickness came from its disequilibrium. Until this larger imbalance was addressed, after a patient was cured, the disease would just hop to another body.

Witches and shamans must attune to the “wild otherness” in their inner and outer landscapes. They must learn to dance and dialogue with this alternate reality in skillful ways. They may take herbs, paint themselves, drum, or sing incantations, but unlike us, they do not doubt their gods and magic are real. This gives them an advantage over us, but we can recover from our handicap. And if we aim to practice astrology as a magical art, the job description now gets clearer. We must meet the planets as living beings and feed the flow of energy between our worlds.

An astrologer’s spiritual neighborhood is of course the sky. Planets are the ones we appease and praise. Charts are the bone-carved dolls we offer. Our rituals involve a deep study of the planets’ positions, their signs, houses, and aspects. But this alone won’t make our practice magical. We must also shift our consciousness and get out of the center of town. We cannot heal or inspire the culture by looking through its jaded eyes. Then the planets will merely be abstract principles hovering above us, stripped of volition and play, nothing more than the shifting gears of a vast machine within which we all grind. Let the sky be our temple. But we need to meet the planets here on earth.

An astrologer’s spiritual neighborhood is of course the sky. Planets are the ones we appease and praise. Charts are the bone-carved dolls we offer. Our rituals involve a deep study of the planets’ positions, their signs, houses, and aspects. But this alone won’t make our practice magical. We must also shift our consciousness and get out of the center of town. We cannot heal or inspire the culture by looking through its jaded eyes. Then the planets will merely be abstract principles hovering above us, stripped of volition and play, nothing more than the shifting gears of a vast machine within which we all grind. Let the sky be our temple. But we need to meet the planets here on earth.

When a hero wants Baba Yaga’s help, he must first approach her cabin and instruct: “Turn your back to the woods, oh hut, turn your front to me.” Then the cabin shudders and starts revolving on its chicken legs until its door faces the hero. How do we interpret this code? If we follow the hero’s example, perhaps we should shout at the planets and tell them to turn our way. This is the typical misdirection of stories that aim to teach magic. We need to look around. It’s not the hero but the hut we should be following. This is where the witch actually lives, with an elevated consciousness, facing away from town, towards the archetypal forest. The hut suggests the proper perceptual attitude for a natural magician: a state of mind that expects the living forces to appear.

So how does an astrologer do this? We put down our charts and textbooks and prepare for live encounters. One day while walking my dog, I was grumbling about something in my life, casually reading the clouds for messages. This is a mystic’s skill but not too extraordinary. You simply soften your gaze and wait to see if a shape in a particular corner of the sky calls your attention. Then you ask your imagination to read it.

That day there was an afternoon Moon, a cloud oddly shaped like Saturn floated nearby; underneath were two clouds that looked like a pair of hands. The phrase “The Moon holds Saturn in her hands” began sounding through my thoughts, until it seeped into the very subject I’d been grumbling about. Before my dog and I reached the baseball field, I was jolted by what now sounds like a rather mundane “Aha!”: I needed to hold my fears and responsibilities (Saturn) with a much deeper compassion (Moon). At the time this idea was quite energetic and successfully turned back my usual self-punishing Moon/Saturn square. When I got home I realized the transiting Moon had just been conjunct my natal Saturn. That precision is interesting—it’s like the planets left me a calling card—but it matters less than the tenderness of the message they wanted me to see.

When you resolve to live facing the archetypal forest, you’ll know you’re doing it right if at times you question your sanity. It’s easy to feel like a fool. You think things you wouldn’t want the neighbors to know—that Jupiter just knocked on your door in the guise of a traveling salesman or Venus dropped a flower on the sidewalk just for you. Feeling a little crazy is a sign that you’re testing the boundaries of ordinary consciousness. You are like the Fool in the Tarot card, eyes raised and heading off the edge of a cliff, with a white flower in your hand. All proper metaphysical journeys begin with this card.

The white flower in the Fool’s hand is actually an emblem for a planet. It is Uranus—Ouranos—the great god of primordial space, the ever renewing source of life’s spiral dance. His message? All the power that ever was or will be is here now. Expect to meet him whenever you’re ready for new creativity or a leap in consciousness.

Recently a woman emailed with this Uranus story: One stormy night, when the messenger Mercury was conjunct her 10th house Uranus, she prayed for guidance and a great ball of blue fire exploded just outside her car window. It was a lightning bolt. She was knocked out, her head was bleeding, her hip was fused to her spine. Shaken as she was and now trapped in the passenger seat, she nonetheless knew the archetypes were visiting. She even managed a little humor and asked, “So is that a yes or a no?” Two weeks later, whenever she closed her eyes, a strange language scrolled through her inner vision. She later translated this into music that eventually went around the world. That was Uranus in her 10th house, traveling on a lightning bolt, bringing its message to the world through her.

Few of our encounters will be this dramatic. But they’ll always be this interesting. Treasure the view from your forest hut.

1 Benson Bobrick, The Fated Sky: Astrology in History (Simon & Schuster, 2005), p. 272

3 David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World, (Vintage Books, 1997)

“The Archetypal Forest” appears in Dana’s Lessons in Astrology as Magic, available as a Kindle book on Amazon.com.

0 Comments