I remember some years ago Michael Harner joking that what he loved about shamanism is that nobody knows what it is. Michael was not just quipping for the sake of quipping, although he did that too. No, he was drawing our attention to an important feature of shamanism, namely, that there will always be some elusive, mysterious quality to it—some elusive and mysterious quality that makes a shaman a shaman. This feature of shamanism that is difficult to pin down or describe becomes even trickier when we consider how widespread and varied shamanic practices are worldwide. Harner’s great legacy to the world is that from those myriad traditions he created a form of shamanism that is accessible to contemporary people who did not grow up in cultures with long established traditions of shamanism. What he called “core shamanism” made it possible for many of us to enter that mysterious and elusive world.

The unknowable quality of shamanism arises from the fact that shamanism connects us to a world of power and spirit, a world that remains substantially invisible and unknowable to us (at least for now). In modern terms, the ability to enter this invisible world requires a shift in consciousness or the creation of an altered state of consciousness. Shamans possess this skill to a remarkable degree which they describe as the ability to journey into the realm of spirits. Researchers into consciousness studies claim two remarkable findings about this realm. The first is that they don’t know what consciousness is! The second is that it permeates the entire universe. In other words, everything is conscious, or “alive,” as shamans would say. Every planet, mountain, blade of grass, grain of sand, rock, weather system, and of course animals and humans—each may have a different kind of consciousness but each manifests from the same source. And each in turn is a source of consciousness with which the shaman communicates.

The unknowable quality of shamanism arises from the fact that shamanism connects us to a world of power and spirit, a world that remains substantially invisible and unknowable to us (at least for now). In modern terms, the ability to enter this invisible world requires a shift in consciousness or the creation of an altered state of consciousness. Shamans possess this skill to a remarkable degree which they describe as the ability to journey into the realm of spirits. Researchers into consciousness studies claim two remarkable findings about this realm. The first is that they don’t know what consciousness is! The second is that it permeates the entire universe. In other words, everything is conscious, or “alive,” as shamans would say. Every planet, mountain, blade of grass, grain of sand, rock, weather system, and of course animals and humans—each may have a different kind of consciousness but each manifests from the same source. And each in turn is a source of consciousness with which the shaman communicates.

Einstein called this consciousness the “superior intelligence whose power reveals itself in the immeasurable universe.” (He also acknowledged that this was his idea of God.) Or we could say it is the Tao which we can’t know directly or name. So what would help us understand this realm of power, of spirits, of intelligence? Many people would probably say that none of this makes sense and figure they might as well give up trying to understand it. But shamans don’t give up. Shamans have used our primary sense, sight, to create a visual environment to focus their consciousness when they wish to tap into the world of spirits. Around the world and throughout time shamans developed cultural artifacts, ceremonies, activities, and places that direct their attention to this world of power. As we might expect, these visual aspects of shamanism can vary greatly. It’s striking that something so esoteric should have so many concrete variations around the world. But it does.

We need something to help us know what shamanism is. Collectively visual images of shamanic activity could provide us with a deeper and more expansive understanding of shamanism. Fortunately there is a new source available that collects this information.

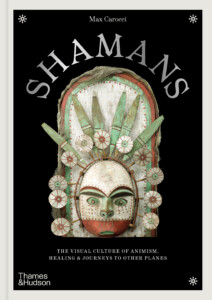

Max Carocci’s Shamans: The Visual Culture of Animism, Healing, and Journeys to Other Places, published by the renowned Thames and Hudson, is a gorgeous companion for anyone curious about the many ways men and women have engaged the world of shamanism. With a long prestigious career in anthropology, art, and museum curatorship, Carocci brings to the many-faceted topic of shamanism deep respect and wide-ranging knowledge. As the title suggests, this book is organized around photos, illustrations, and artwork derived primarily from indigenous sources, but it also acknowledges the ways that practitioners of core shamanism and other modern variations of shamanism practice the art. And not to be overlooked is the author’s intelligent and engaging text that presents this difficult topic in a way that will interest both newcomers to shamanism as well as people well-versed in it. His observations about things I thought I already knew expanded and deepened my understanding of them.

Max Carocci’s Shamans: The Visual Culture of Animism, Healing, and Journeys to Other Places, published by the renowned Thames and Hudson, is a gorgeous companion for anyone curious about the many ways men and women have engaged the world of shamanism. With a long prestigious career in anthropology, art, and museum curatorship, Carocci brings to the many-faceted topic of shamanism deep respect and wide-ranging knowledge. As the title suggests, this book is organized around photos, illustrations, and artwork derived primarily from indigenous sources, but it also acknowledges the ways that practitioners of core shamanism and other modern variations of shamanism practice the art. And not to be overlooked is the author’s intelligent and engaging text that presents this difficult topic in a way that will interest both newcomers to shamanism as well as people well-versed in it. His observations about things I thought I already knew expanded and deepened my understanding of them.

I found Carocci’s organization of this voluminous material to be well constructed to tease out the various aspects of shamanism. He begins with the foundational principles that underly an animistic cosmos and the intricate ways that animistic beliefs interact with what we view as religion. I’m sure his treatment of this will appeal to everyone who has wondered (or had to explain) how animistic worldviews constitute a legitimate spirituality. How experiencing a universe that contains spirits can be as meaningful and comforting as traditional religious beliefs.

The second section of this book looks at a key characteristic of shamanism, namely, the shaman’s understanding that the cosmos consists of various realities and that there are methods for communicating and entering those realities. Again, readers will find the author’s explanation of these difficult topics clear and understandable, and reassuring that shamanic practitioners are not crazy or delusional in their work. Carocci is a gifted writer who can make non-ordinary realities seem, well, ordinary without losing their otherworldly enchantment.

The final section of the book addresses the material infrastructure of the shaman’s world: drums, rattles, clothing, masks, mirrors, power objects, sacred plants, and so forth—the various instruments for practicing shamanism that are found in disparate parts of the world, lavishly presented in colorful illustrations and photographs. Throughout there are pictures and explanations of ancient artifacts as well as artwork by contemporary indigenous artists. Also included here are the physical ways that shamans use their bodies in sacred work, such as trance, dance, cross-dressing, sensory deprivation, and bodily suffering as in piercing the skin with sharp objects. Carocci also discusses what he calls “places and spaces”: natural sites, rock art, megalithic formations, ceremonial venues long considered to be power spots, and even places that the neo-shamanic world creates for ceremony and healing, like living rooms. Yes, throughout the book there are reminders that shamanism has always been evolving, and that modern practices can be just as authentic as those descended from original peoples.

One of the joys of this book is that it never stopped surprising me with its attention-gathering juxtaposition of aspects of shamanism I would not have expected to encounter. A medieval print of St. George slaying the dragon. A1946 photo of an entranced snake-handler in Kentucky. A female Korean shaman collapsed during a trance. Bernini’s seventeenth century sculpture, The Ecstasy of St. Teresa. Rock and cave art from around the world. Early European depictions of shamans as they were first encountered. Revived shamanic traditions from various parts of old Europe. A 1959 photograph of Italian musicians playing the tarantella to heal a woman bitten by a tarantula. A Mongolian shaman fighting invisible forces. A sidebar decoding a Taino votive effigy. As well as striking colored photographs of shamanic traditions and practices from Africa, Asia, North and South America, India, Europe, Australia, and lesser-known islands with strong shamanic traditions. There’s even a1978 photo of Mircea Eliade (himself!) sharing space with contemporary photographs of shamans in Indonesia, Mongolia, Ecuador, Africa, Venezuela, the Himalayan region, Russia, the Philippines, California, Washington State, and Liverpool—and many more too numerous to mention.

One of the joys of this book is that it never stopped surprising me with its attention-gathering juxtaposition of aspects of shamanism I would not have expected to encounter. A medieval print of St. George slaying the dragon. A1946 photo of an entranced snake-handler in Kentucky. A female Korean shaman collapsed during a trance. Bernini’s seventeenth century sculpture, The Ecstasy of St. Teresa. Rock and cave art from around the world. Early European depictions of shamans as they were first encountered. Revived shamanic traditions from various parts of old Europe. A 1959 photograph of Italian musicians playing the tarantella to heal a woman bitten by a tarantula. A Mongolian shaman fighting invisible forces. A sidebar decoding a Taino votive effigy. As well as striking colored photographs of shamanic traditions and practices from Africa, Asia, North and South America, India, Europe, Australia, and lesser-known islands with strong shamanic traditions. There’s even a1978 photo of Mircea Eliade (himself!) sharing space with contemporary photographs of shamans in Indonesia, Mongolia, Ecuador, Africa, Venezuela, the Himalayan region, Russia, the Philippines, California, Washington State, and Liverpool—and many more too numerous to mention.

I wonder if Michael Harner is still watching us. I’m sure he would be pleased with this beautiful book. It makes a fine addition to the library of shamanism. But I suspect he would still insist that no one really knows what shamanism is. It’s just too mysterious. That’s okay. Whether you’re new to shamanism and just getting your feet wet or whether you’ve been splashing around in shamanism for years, perhaps it doesn’t matter if you don’t know what it is. Maybe what’s important is the unending quest to find out. Get a copy of this book. It will help.

A very interesting, enjoyable and educational read. Thank you, Tom.

The state of Shamanism has, in moden times, been virtually unknowable to the majority of humans due to the rigid parameters ingrained and accepted into the human mind.

It takes a leap of faith, yes, and ….. it also requires a letting go of our attachment to our own deeply habitual,

human identity to which we are so tightly imprisoned.

Earlier man walked more loosely and open upon our sacred Earth, and knew himself to be an equal member of Her tribes, as each has their own Wisdom and Reason to Be.

Therefore, the willed act of parting the Veil, ‘slipping away’, and changing our valence was much more natural and productive.

Ones can study Shamanism – but to be a Shaman requires a true, living experience, from which much benefit can be had for all the forms of Life.

It has long been shown to me that many of the citizens of the ‘Otherworlds ‘ are mostly very willing to partnership with the Human Lifeform. But, exercising strict discrimination on our part is fundamental to a successful cooperation and outcome during this tandem state of ‘beingness’.

Knowing ourselves to be a valuable piece in Nature’s puzzle, not Her dominator or controller, is paramount for the furtherance of life for all species on Earth.

May we always walk with Great Honor and Integrity.